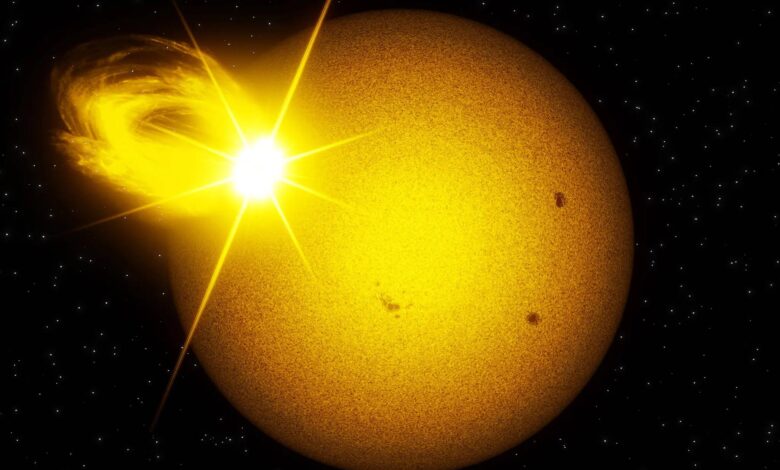

Our sun is a turbulent place. Explosive rays are released from the surface of the Sun with the power of millions of volcanic eruptions. The hot plasma boils and spews out particles that can harm astronauts and satellites in space and destroy power systems on Earth. At the same time, these particles can illuminate the sky of our planet with colorful light effects.

But scientists have observed much larger explosions with the power of a trillion hydrogen bombs in other stars and named them “superflares”. Although no superflares have yet been observed in our own Sun, scientists have wondered whether our own star is capable of producing such incredibly powerful flares, and if so, when it might do so.

A paper published last Thursday in the journal Science provides more information about superflares. In their study, researchers have concluded that stars similar to the Sun produce very powerful flares approximately once every hundred years. Such an estimate is much higher than expected and suggests that we may be seeing an extremely powerful solar event sooner or later.

Superflares are being produced at a rate of about one per century, at least 30 times higher than previously estimated

Yuta Notsu, an astrophysicist at the University of Colorado Boulder and one of the authors of the paper, says: “We live in the space age; As a result, I think it’s good to estimate low-probability but high-impact events” so that space weather experts can better gauge the potential dangers facing our planet.

Solar flares occur when the Sun’s magnetic field lines become entangled and collapse, releasing a burst of energy into space that is often accompanied by an ejection of charged particles. If these particles interact with the Earth’s atmosphere, the effects of that solar event can be left in tree rings or ice cores.

But particles aren’t always ejected, and the sun’s explosive events don’t always come toward our planet. For this reason, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the Sun’s behavior from natural effects on Earth. Valery Vasiliev, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany who led the study, says a better way to find out whether our Sun is capable of producing superflares is to look at stars that behave like it in the Milky Way. .

Using data from NASA’s now-retired Kepler space telescope, Dr. Vassiliev’s team identified stars with similar temperatures, sizes, and brightness patterns to the Sun. searched Out of 56,450 Sun-like stars, they found that one in 20 produced super-strong flares.

According to the researchers’ conclusions, the production of superflares at a rate of approximately one per century is at least 30 times higher than previously estimated. Dr. Vasiliev describes this difference as very impressive and surprising.

One reason the rate obtained in the recent study may be much higher than expected is that the researchers used higher-resolution image analysis, which allowed them to more accurately match the observed flares to their host stars.

read more

Scientists also now have a better idea of what makes a star look like the Sun; Especially after the publication of a study in 2020 that showed that our sun is not as active as previously thought; This means that superflare rates calculated in the past may have been done by examining a sample of stars that were not truly representative of the group that includes our Sun.

Hugh Hudson, an astronomer at the University of Glasgow in Scotland who was not involved in the study, applauds the researchers’ new method of matching flares to their host stars. However, he is not convinced that the frequency of superflares is really that high. For Hudson, the question remains whether the sample of stars examined is truly representative of our Sun, especially in terms of how brightness changes over time.

In the future, the researchers plan to compare their results with observations from other space telescopes, including NASA’s exoplanet mapping satellite and the European Space Agency’s Plato spacecraft, which is scheduled to launch in 2026. They also hope to reanalyze using X-rays and ultraviolet light to compare their measurements at different wavelengths.